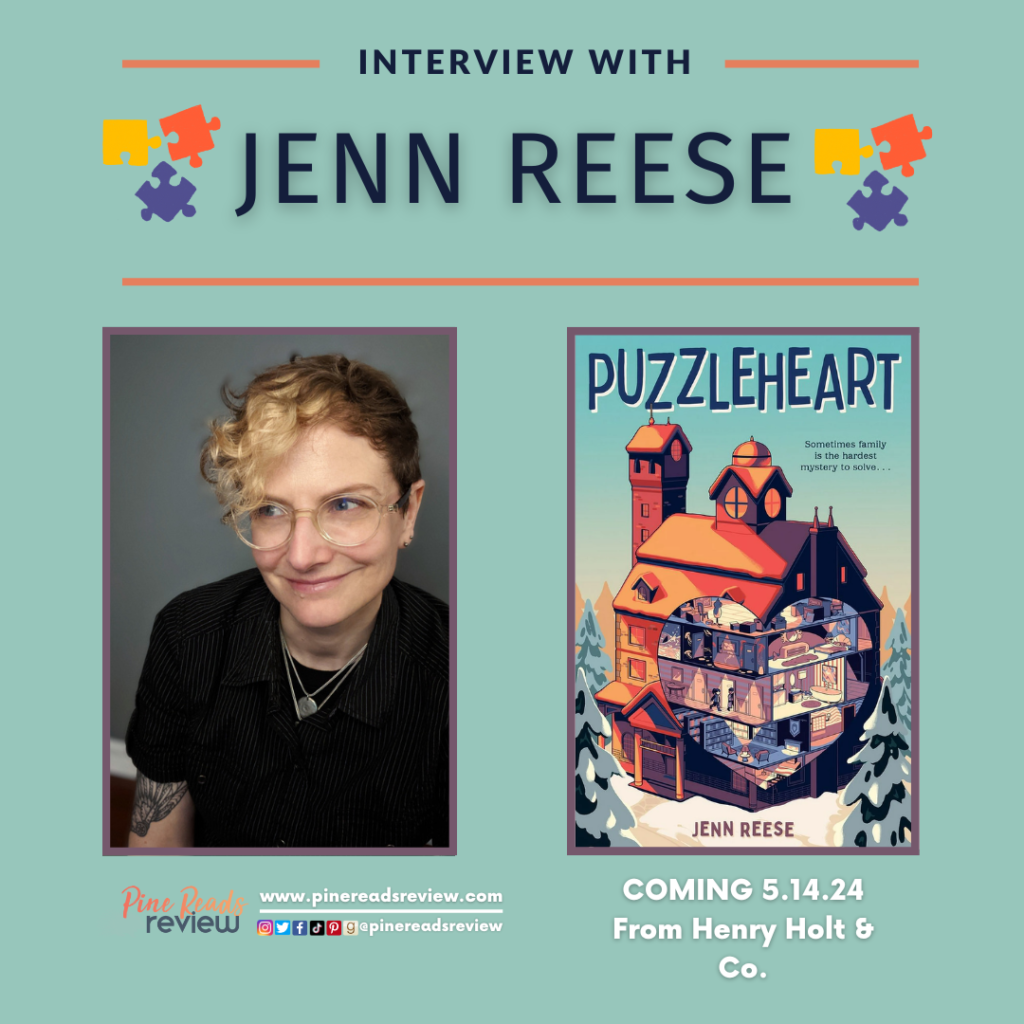

About the Interviewee: “Jenn Reese (they/she) writes speculative fiction for readers of all ages. Jenn is the author of Puzzleheart, Every Bird a Prince, the Oregon Book Award-winning A Game of Fox & Squirrels, and the Above World trilogy. They also write short stories for teens and adults. Jenn lives in Portland, Oregon where they make art, play video games, and build cardboard forts for their cats” (Bio from the author).

Find Jenn Reese on the following platforms:

Jenn Reese: Thanks for having me! My answer for this one has three parts. First, I think kids in that 10-14 zone are living with major upheavals. They’re hitting puberty, they’re changing schools, they’re experiencing a shift from being kids to young adults. It’s exciting, and it’s terrifying, and it’s massively confusing, even on the good days. I like to think of my books as tiny life preservers tossed into that tumultuous ocean, little spaces where they can feel safe and have a little fun. Second, I’m generally writing books I wish I’d been able to read as a kid that age. And third, young readers are the best! They are so passionate about reading and don’t hesitate to tell you if they love your work or if “It’s not as good as Percy Jackson.” The capacity for wonder is a treasure, and most middle grade readers are rich with it.

JR: I was not one of those kids who knew they’d be a writer. I wanted to be an artist, and then a particle physicist, and then a computer scientist. I didn’t start writing short stories until I was almost 30, and I didn’t attempt my first novel until years after that. On the other hand, I have always loved creating. I discovered Dungeons & Dragons when I was twelve and began creating characters and worlds and magic items. I was training for my future job without even knowing it.

JR: I have always loved puzzles and games. I love how my brain feels when it’s working hard to unknot a tangled mystery. Ellen Raskin’s The Westing Game is one of my favorite books of all time, and, while I’ll never attain the brilliance of that book, I can’t help but continue trying to capture a little of its magic. As for more recent inspiration, I play a lot of video games, and the puzzle genre is one of my favorites. I also love board games, the New York Times crossword, and basically anything that might lead to one of those intoxicating “A-ha!” moments.

JR: Families take so many shapes these days, but we still seem obsessed with biology, with fitting the strange, beautiful shapes back into the square boxes we’ve been taught to look for. A lesbian couple might be asked about their sperm donor, for example, when that person has no connection to either of them or their child. In Puzzleheart, Perigee does not have a “mother” in any traditional sense, and that’s okay. I don’t mention it because I think we should start training ourselves not to ask. (And I include myself in this—I still do it as much as anyone!)

JR: I am certainly not an expert on grief. All I can speak to is the corrosive power of denial. If we don’t acknowledge pain and loss, if we don’t talk about it, then it hides deep inside us, waiting to ambush us when we’re tired or feeling low. It takes tremendous energy to keep it tamped down all the time, and no one can be that strong forever. In my own life, I rely on therapists. When my partner was diagnosed with cancer, our therapist suggested we “normalize” the fear and grief by talking about it. We developed a rule that we had to say the word “cancer” at least three times a day until it became like any other word. But grief is its own beast, and everyone will deal with it differently. My best advice is not to face it alone.

JR: I don’t think it’s a child’s responsibility to care for the mental health of their parent. I think most children are sensitive to their parent’s mental state and that they’ll want to help if their parent is struggling, but ultimately, that responsibility lies with the parent. Kids have enough to deal with in their own tumultuous lives and often their own mental health issues to navigate.

JR: Oftentimes, I write books about themes I want to explore for myself. In Puzzleheart, I was interested in two ideas: the way we sometimes turn ourselves inside out to help when our loved ones are hurting and the idea that mental health issues can make us feel “broken.” The story changed as I was writing and exploring those ideas and as the House developed as a character. It became more and more important to me to reject the idea of “brokenness.” The line I had written in my notebook was, “People are not puzzles; they cannot be ‘solved.’” I ended up with a lesson for myself: We need to accept and support people as they are. We need to relinquish the idea that we can “fix” their problems, both for their sake and for ours.

JR: I have adopted my fair share of kittens, and I am primarily drawn to two types: the troublemaker and the shy one. In fact, I have those two cat archetypes in my family right now! I have a sweet gray-and-white boy named Oslo who requires soft words and no sudden movements but will love you to pieces if you sit perfectly still. And I have Finley, an orange boy who is far too brilliant for his own good. He locks himself in rooms, opens cabinets, and can get any piece of food out of any container. In Puzzleheart, Banana has already won everyone over. I’d scoop up the smallest, quietest kitty of the bunch, a little gray tabby, and name her Cataclysm.

JR: Creativity is a muscle—exercise it, and it gets bigger! This year, for example, I have a calendar where I’m writing a new first sentence or two every day right in the calendar square. It’s such a small space that it’s not intimidating, and yet I can feel my creative muscles warming up, even when the sentences are terrible. (Here is my January 1st sentence, which you are welcome to: “On Friday, the octopi walked out of the ocean. All of them. Every last one.”) As for rejection, yeah, it can be tough. One trick is to focus on the process, not the results. I celebrate rejections as proof that I’m doing the work. After I sold and published my Above World trilogy, I failed to sell the next four books I wrote—five years of work! But in the end, I was still proud of those books and myself. I hunkered down and practiced my craft and improved. I ended up changing my novel writing process to see if it would breathe new life into my stories. The next book didn’t sell either, but the one after that did. Another trick is to find your writing people. Commiserate, give yourself challenges, make it a game. Enjoy each other even if the publishing industry is no fun. I would personally give up writing before I gave up my writing friends. Good luck to all you writers!

JR: I’ve been in a creative purgatory since finishing Puzzleheart. I’m toying with several ideas, playing with characters and first chapters and themes, but I haven’t found a story that sets my fingers on fire yet. I did sell my first picture book, which will hopefully be out in 2025, but it hasn’t been announced yet. In the meantime, I’m “filling the well” with drawing, ceramics, video games, and guitar. I’m hoping to write some poems and songs this year, which will undoubtedly be very bad, but I don’t mind. Being bad at something is a kind of freedom. Thank you so much for these wonderful questions!

Emilee Ceuninck, Pine Reads Review Lead Writer